A brief outline of the history of tattooing in Europe

Hannah T. Wagner, November 2020

Historical tattoos are often associated in the “western world” with faraway countries and strange cultures. However, the oldest evidence of tattooed human skin comes from South Tyrol, in the heart of Europe. In 1991, the mummified body of a man was found in the Oetztaler Alps (we know him as “Ötzi”) whose skin showed numerous tattoos. Radiocarbon dating showed that the mummy was around 5300 years old. Ötzi’s tattoos were possibly for medical purposes, as they were found on parts of his body where physical problems were proven. However, the purpose and meaning of the tattoos is no more than speculation. The tattoos were presumably created by scratching or poking the skin, and rubbing soot into the wounds.

Tattoos of a similar age have been found in many places, such as Egypt, where the practice of mummification preserved several such examples. Unlike Ötzi’s tattoos, the Egyptians had not only geometric patterns, but also figural designs.

Some especially imposing examples of tattoos preserved by mummification included an unknown, around 3000-year-old female mummy, which was discovered in Deir el-Medina, Egypt, in 2014 – and Princess of Ukok, who was discovered in 1993, around 2500 years after her death in the Republic of Altai in Siberia.

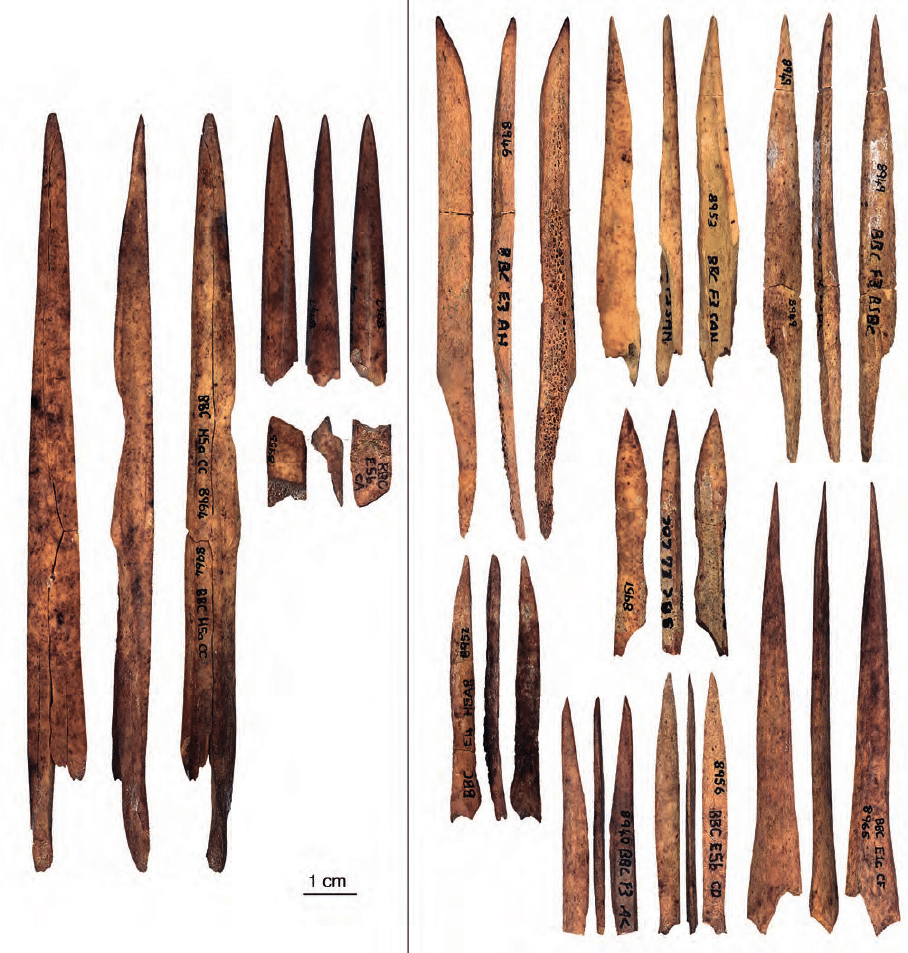

However, tools associated with creating tattoos have appeared far earlier, dating back 76,000 to 84,000 years. In 1991, sharpened bone fragments were found in the Blombos cave in South Africa with traces of ochre on their tips, which indicated their possible use.

It is considered very likely that the people mentioned above were tattooed of their own free will, for medical, ritual, decorative, or religious reasons.

In ancient Greece or Rome, by contrast, it was common to use tattoos as punishment or a mark of ownership. This practive was restricted to slaves, and is connected with the word “stigmatisation” (Stigma, literally “to mark, brand”) and was so widespread that slaves were also known “inscriptus” (inscribo, “something bearing writing”) or “litteratus” (“marked with letters”). Members of early Christian societies who survived their enslavement considered their punitive tattoos as signs of their martyrdom and had Christian symbols tattooed or burned on their skin as proof that God rescued them (Iris Därmann, Unter die Haut. Tätowierungen als Logo- und Piktogramme, Paderborn 2017, S. 33).

The free Greeks would not consider tattoos, they were something “barbaric” that marked their tattooed enemies, criminals and slaves.

The association with otherness and criminality only flared up in Europe again in the middle of the 19th century. Based on a German criminal case, several European scientists started studies to separate the “working class” from a “dangerous class, however always under the assumption that people with tattoos are antisocial and dangerous” (Eero Wahlstedt, Tattoos and Criminality, St. Petersburg 2010, Introduction).

Systematic documentation on tattoos at the time was only available for identification purposes, and this mostly affected criminals, sailors and soldiers. There is no way to know how prevalent tattoos were in the total population.

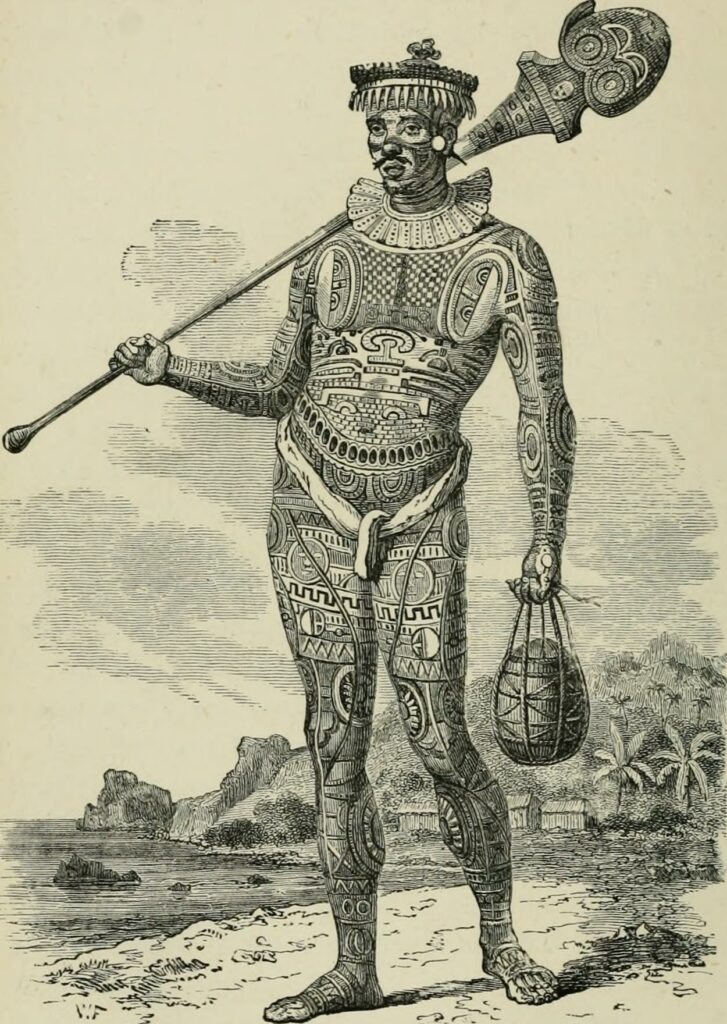

In the mid-18th century, Captain James Cook of Britain brought the Polynesian term “Tatau” back from his expeditions in the South Pacific. This is the origin of the word “Tattoo”. The so-called “Cook Myth” says that tattooing as it is practised today is a direct result of the European expansion into the South Pacific.

While the tradition of seafarer tattoos grew more prevalent (also an association with people on the fringes of society), tattoos had actually never disappeared from Europe, and continued to carry the negative connotation in part from antiquity.

From the 15th to the 19th century, tattoos were especially common on pilgrims marking their pilgrimages – a tradition which presumably already started in the days of the crusades. The designs were mostly premade with Christian symbolism, which were applied to the skin in part with wooden stamps. There is also evidence of individual tattoos from this time with no religious significance, but rather to honour monarchs and rulers.

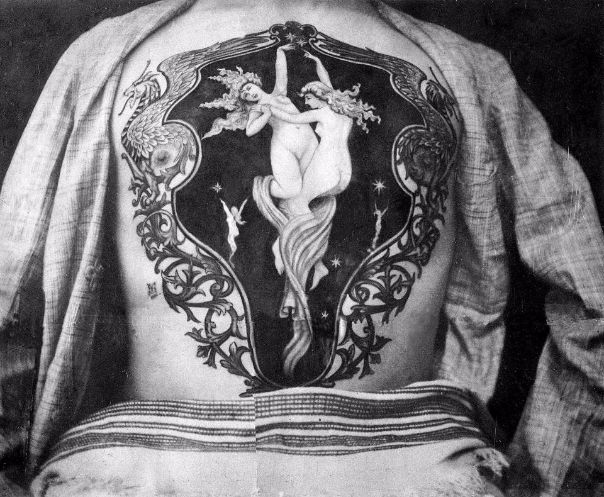

In the 1880s, a regular tattoo boom took place in Britain. This occurred in part because it came to light that some aristocrats, including some members of the Royal House, had tattoos. At around the same time, the first tattoo machines were patented, which of course contributed to the uptick in popularity. In 1894, Sutherland Macdonald opened the first tattoo studio in London and, according to folk anthropologist Adolf Spamer, enjoyed the reputation of being a great artist, even referred to the European “Raffael” among tattoo artists.

A trend towards full-body tattoos emerged among Europeans, which was often in connection with displaying of the body, and the associated income. Tattooed people had long been part of the attractions in circuses and travelling variety shows. However, these were kidnapped indigenous people, who were ripped away from their homes and displayed like zoo animals. Many of these people died after a short time, often of European diseases (source: Stephan Oettermann, Zeichen auf der Haut, Frankfurt a. M. 1979, p. 28), similar to the so-called “human zoos” in the “people’s exhibitions”.

At the start of the 20th century, many tattooed people in Europe and the US, especially women, earned their keep by displaying their bodies in circuses or private establishments. In 1911, tattooed German woman Marie Finke was banned from displaying herself at a locale she rented for this purpose in Berlin (Tägliche Rundschau, 5. February 1911) – so-called “moral decency” was on the rise, as well as concerns about hygiene. This led to people concealing tattoos more and fewer tattoos being done.

In Nazi Germany, the idea of tattoos as a way to convey identity and individuality was perverted in the concentration camp in Auschwitz, where people were forcibly tattooed with numbers. This was aimed at erasing the individual, making them numbers instead of people. After World War II, the survivors proudly showed their numbers as a sign of strength in surviving the horrors of the camps.

The post-war period ushered in a middle class for whom tattoos had no meaning. Via the outsider culture of the 1950s, the subculture of the 60s, and finally into pop culture and the mainstream in the 70s, the tattoo is experiencing a renaissance which has lasted longer than its previous episodes.

Tattoos have been prevalent over many cultures and great time periods and are in many places considered a positive status symbol, which can symbolise family and clan affiliation, be symbolic of achievements, or be part of an initiation ritual. It seems that historic negative connotations have done little to dim people’s fascination with this ancient art and art form.